Of Lights and Ruins

Pojai Akratanakul, 2025

Martin Constable’s work, be they paintings or digital prints, transport us to a different universe. A sense of familiarity probably derives from recognizable shapes, yet we cannot determine whether the images depict our world post-apocalypse, or of a completely different one.

What is certain, however, is that each of Constable’s images depicts a situation where our perception of time is rendered obsolete. The image is not from the past and not bound to the predictable 24/7 standard. Imagine that the one minute contained in the image is no longer our known 60 seconds. Time here functions differently. It may be burning, or it may stand still. The warped temporalities hint at an existential crisis.

In the manner of the Hudson River School and the Romantic painters, Constable’s work evokes a spirit of exploration. The symbols within his pieces—from lights and wreckages to skeletons—hold meaning, but they do not demand to be interpreted or fully understood. Instead, they call for a deeper emotional contemplation on existence: the artist’s, our own, and that of humankind. This survey exhibition of Constable’s works from the past decade could be viewed as an exploration of our fear of forgetting and the act of remembering–what we have registered as history.

In the Event of a Moon Disaster

“These two men are laying down their lives in mankind’s most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding. […] Man’s search will not be denied. But these men were the first, and they will remain the foremost in our hearts.”

A memo prepared for President Nixon in 1969 recorded a speech to be delivered should the Apollo 11 mission fail [1]. Though the speech was never used and now exists only as an archival document, the themes of searching for truth and understanding resonate with Constable's work. In A Fragment of an Interrogation (2025), the artist adapts the memo's layout to record a conversation between a man and an unidentified being pondering life's expiration. Its satirical content is self-explanatory, while implying a sense of cosmic horror, fear of humanity's insignificance.

Lacking specific identifications, the conversation is without authorship, much like the paintings The Man Who Asked Why (2025) and In League With His Demons (2024). Both scenes omit the presence of the ‘Who,’ yet what is tangible are the tools belonging to someone who creates.

This idea extends to the painting of worn boots titled Half Way There is Half Way Gone (2025), which could symbolize a journey and the passage of time. It recalls a famous art debate of Vincent van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes (1886) and Walker Evans’s Floyd Burroughs's Boots (1936), which were central to Heidegger’s The Origin of the Work of Art, and later criticized by Derrida and many others [2]. The 'true' identity of the owner of the boots, the context that frames them, the ‘Why’, remain obscured.

Starfield, Screensaver Subterfuge, and Descent

The screensaver was invented in 1983 as a tool to prevent burn-in on older monitors during idle periods. In 1995, Windows released its iconic Screensaver Subterfuge, a first-person experience of endlessly wandering a 3D maze of red brick walls. When the user encounters a gray rock, the view flips, causing a sense of disorientation and a feeling of being in an abyss.

Likewise, Constable's digital prints and videos recall the visual language of screensavers. The God of Details (2025) series presents quiet scenes of various spaces from a messy workshop to a sterile museum that is completely devoid of people. They could be modeled from the artist’s memory or may not exist at all. Yet, the small details—a leftover plate, a lined trash bin, a wrinkled carpet—show subtle touches of beings. The perfectly rendered lights are on, illuminating certain objects. Are these images from the quiet of the night? Can we consider them as in-between spaces—an interval, an elevator, a screensaver, or an airport? A space that anticipates something…

Or, perhaps, are they images of an aftermath? Much like the wrecked motorcycle in the painting The Mix (2025), which depicts a journey interrupted. Did someone flee these scenes after a significant event, a kind of doom? Are these moments of an apocalypse, or is time simply paused? There is no knowing what actually happened. While the stillness in these images offers a sense of solitude, their computational sharpness and super-resolution allude to an underlying sense of control and anxiety.

Two videos on loop, Try Again. Fail Again. Fail Better. (2024) and ...Not For the Fire in Me Now (2022), present interior views from the cockpits of spaceships. The first-person perspectives, with its visible control panels and buttons, place the viewer in the pilot's seat. Looking closer, the views from the windows reveal not the scenery of our world, but of outer space.

Nauseating and disorienting, these videos of no more than five minutes render a moment of destruction. Upon recognizing the audio adapted from the black boxes of actual historical flights, the videos become even more sensorially disturbing. The disorientation is beyond being sucked into the void of a Starfield screensaver or playing the flight simulator Descent (1995), inflicting overwhelming vertigo and anxiety.

Future History

“How are we writing the future of humanity? We’re not writing anything, it’s writing us. We’re windblown leaves. We think we’re the wind, but we’re just the leaf. [...] Aren’t we so insecure a species that we’re forever gazing at ourselves and trying to ascertain what makes us different. We great ingenious curious beings who pioneer into space and change the future, when really the only thing that humans can do that other animals cannot is start fire from nothing.”

Martin Constable is attracted to crashes and ruins. His obsession with destruction partly stems from personal trauma, but also from seeing it as a process that reveals the structure and true nature of things [4].

For example, Rebes Minor (2021) takes half of its title from how astronomers name constellations. The decaying ruins, inspired by medieval castles from Game of Thrones, tell a satirical story of a competing academia from another world where teachers are killed and schools are burned [5]. But within this darkness, a small ray of hope, a flickering light, is placed in the center.

Many of the paintings selected offer a ritualistic scene of watching and highlight the importance of light. Lustrum (2024) presents a lone figure staring into a fire, humanity’s earliest technology. To master the control of fire was a monumental leap, the same as sending humans into space. To stare into light sources, albeit a candle, or the moon, is also a symbolic gesture [6]. A collective gathering to gaze at something together, as in Raze (2024) and The Invention of Grief (2024) is even more momentous. In this context, these paintings become contemporary rituals.

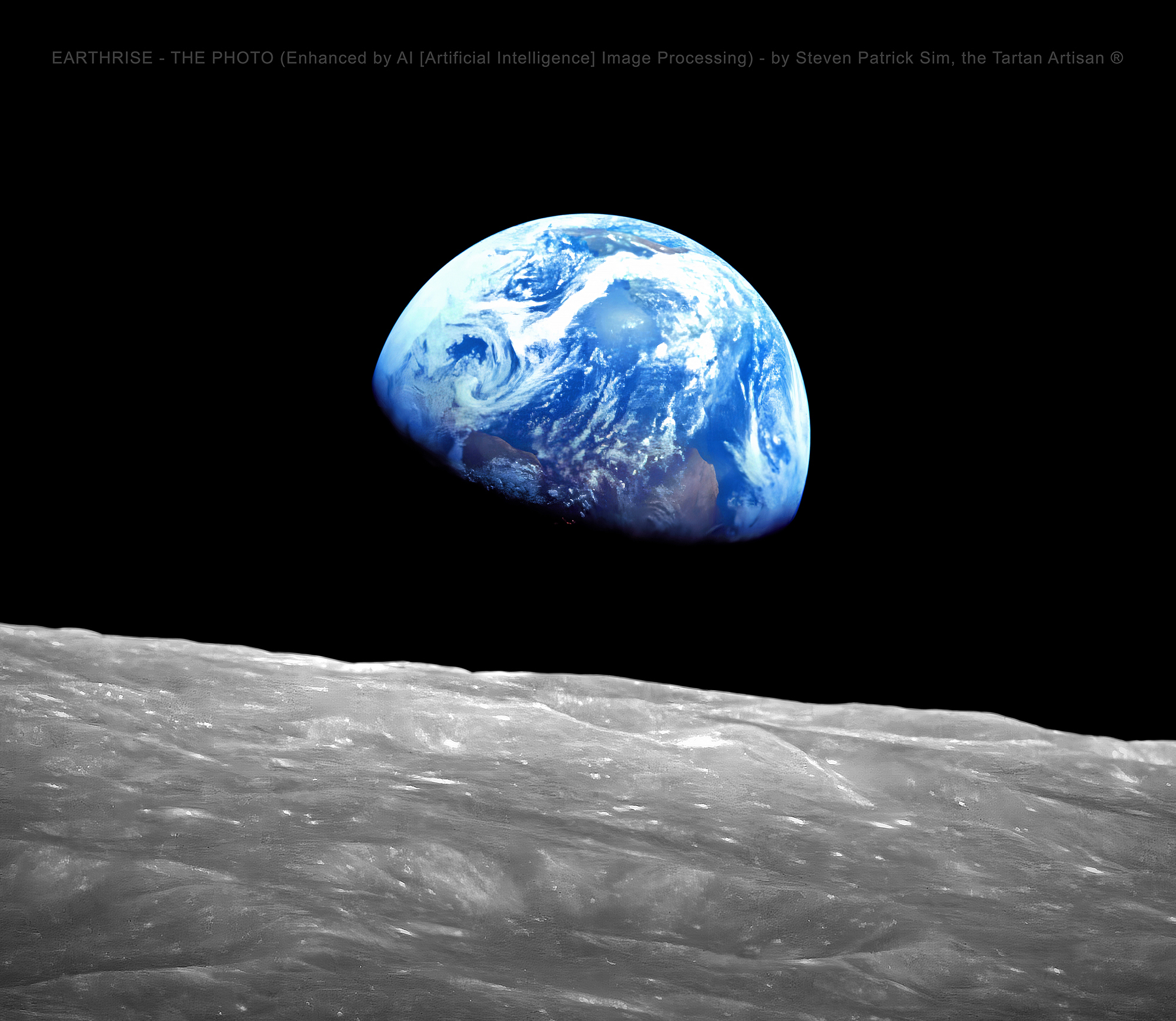

Lastly, What He Left Behind (2025) is a simple first-person view of a planet. It recalls the historical photo Earthrise (1968) taken by Astronaut Bill Anders from the Apollo 8 mission. Anders famously remarked that "We went to the moon to explore the Moon, but what we discovered was the Earth." The painting stresses this same profound moment, triggering a humbling awareness of our small presence against the cosmos.

Coda

A selection of works for What Cannot Be Forgotten, Must Be Celebrated delves into dark emotional states and somber scapes, excavating a deep contemplation on existence, while inviting us to confront the same questions for ourselves.

This contemplation culminates in the final piece, Qua-Auq (2015) where Constable digitally recreates the skull of Lam Qua (1801–1860), a Chinese painter known for being the first to adopt a Western style for his medical illustrations. By placing the skull in a vitrine that references the National Museum of Singapore, Constable again examines the very existence of the artist and the human desire to be remembered, and to leave something behind.

![]()

Earthrise taken by William Anders on Dec 24, 1968. Image credit: NASA. [7]

1. William Safire, "In Event of Moon Disaster," memorandum to H. R. Haldeman, July 18, 1969, Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, National Archives and Records Administration. Source: https://www.archives.gov/files/presidential-libraries/events/centennials/nixon/images/exhibit/rn100-6-1-2.pdf, accessed 2 September 2025.

2. Martin Heidegger used Vangogh’s Pair of Shoes to illustrate his point that art reveals the “truth of being,” because the shoes belong to a peasant woman, the image alone in a phenomenological sense reveals another world that belongs to the peasant, therefore the shoes are not just objects, but “equipmental being of equipment,” belonging to another context (1936). While Meyer Schapiro criticized Heidegger that the shoes were not of the peasant’s but Van Gogh’s own, therefore biographical (1968). Derrida criticized both of them that they viewed the shoes from a lens trapped in representations and imposing meanings onto the shoes that they must belong to a specific, rather than seeing the art in its own right. In this debate, Evan’s photograph of actual boots from the Great Depression is frequently used in comparison with Van Gogh’s, since it belongs to a person, while Van Gogh is a painterly representation. Source: Brian Goldberg, “Two Boots and Four Portraits,” RISD Museum, January 28, 2019, https://risdmuseum.org/art-design/projects-publications/articles/two-boots-and-four-portraits. Accessed September 2025.

3. Samantha Harvey, Orbital (London: Jonathan Cape, 2023), 106.

4. Martin Constable, interview by the author, online document, July 2025

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Earthrise: A Conversation with Apollo 8 Astronaut Bill Anders, December 29, 2023, video, https://plus.nasa.gov/video/earthrise-a-conversation-with-apollo-8-astronaut-bill-anders. Accessed 6 September 2025.

What is certain, however, is that each of Constable’s images depicts a situation where our perception of time is rendered obsolete. The image is not from the past and not bound to the predictable 24/7 standard. Imagine that the one minute contained in the image is no longer our known 60 seconds. Time here functions differently. It may be burning, or it may stand still. The warped temporalities hint at an existential crisis.

In the manner of the Hudson River School and the Romantic painters, Constable’s work evokes a spirit of exploration. The symbols within his pieces—from lights and wreckages to skeletons—hold meaning, but they do not demand to be interpreted or fully understood. Instead, they call for a deeper emotional contemplation on existence: the artist’s, our own, and that of humankind. This survey exhibition of Constable’s works from the past decade could be viewed as an exploration of our fear of forgetting and the act of remembering–what we have registered as history.

In the Event of a Moon Disaster

“These two men are laying down their lives in mankind’s most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding. […] Man’s search will not be denied. But these men were the first, and they will remain the foremost in our hearts.”

Bill Safire [1]

A memo prepared for President Nixon in 1969 recorded a speech to be delivered should the Apollo 11 mission fail [1]. Though the speech was never used and now exists only as an archival document, the themes of searching for truth and understanding resonate with Constable's work. In A Fragment of an Interrogation (2025), the artist adapts the memo's layout to record a conversation between a man and an unidentified being pondering life's expiration. Its satirical content is self-explanatory, while implying a sense of cosmic horror, fear of humanity's insignificance.

Lacking specific identifications, the conversation is without authorship, much like the paintings The Man Who Asked Why (2025) and In League With His Demons (2024). Both scenes omit the presence of the ‘Who,’ yet what is tangible are the tools belonging to someone who creates.

This idea extends to the painting of worn boots titled Half Way There is Half Way Gone (2025), which could symbolize a journey and the passage of time. It recalls a famous art debate of Vincent van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes (1886) and Walker Evans’s Floyd Burroughs's Boots (1936), which were central to Heidegger’s The Origin of the Work of Art, and later criticized by Derrida and many others [2]. The 'true' identity of the owner of the boots, the context that frames them, the ‘Why’, remain obscured.

Starfield, Screensaver Subterfuge, and Descent

The screensaver was invented in 1983 as a tool to prevent burn-in on older monitors during idle periods. In 1995, Windows released its iconic Screensaver Subterfuge, a first-person experience of endlessly wandering a 3D maze of red brick walls. When the user encounters a gray rock, the view flips, causing a sense of disorientation and a feeling of being in an abyss.

Likewise, Constable's digital prints and videos recall the visual language of screensavers. The God of Details (2025) series presents quiet scenes of various spaces from a messy workshop to a sterile museum that is completely devoid of people. They could be modeled from the artist’s memory or may not exist at all. Yet, the small details—a leftover plate, a lined trash bin, a wrinkled carpet—show subtle touches of beings. The perfectly rendered lights are on, illuminating certain objects. Are these images from the quiet of the night? Can we consider them as in-between spaces—an interval, an elevator, a screensaver, or an airport? A space that anticipates something…

Or, perhaps, are they images of an aftermath? Much like the wrecked motorcycle in the painting The Mix (2025), which depicts a journey interrupted. Did someone flee these scenes after a significant event, a kind of doom? Are these moments of an apocalypse, or is time simply paused? There is no knowing what actually happened. While the stillness in these images offers a sense of solitude, their computational sharpness and super-resolution allude to an underlying sense of control and anxiety.

Two videos on loop, Try Again. Fail Again. Fail Better. (2024) and ...Not For the Fire in Me Now (2022), present interior views from the cockpits of spaceships. The first-person perspectives, with its visible control panels and buttons, place the viewer in the pilot's seat. Looking closer, the views from the windows reveal not the scenery of our world, but of outer space.

Nauseating and disorienting, these videos of no more than five minutes render a moment of destruction. Upon recognizing the audio adapted from the black boxes of actual historical flights, the videos become even more sensorially disturbing. The disorientation is beyond being sucked into the void of a Starfield screensaver or playing the flight simulator Descent (1995), inflicting overwhelming vertigo and anxiety.

Future History

“How are we writing the future of humanity? We’re not writing anything, it’s writing us. We’re windblown leaves. We think we’re the wind, but we’re just the leaf. [...] Aren’t we so insecure a species that we’re forever gazing at ourselves and trying to ascertain what makes us different. We great ingenious curious beings who pioneer into space and change the future, when really the only thing that humans can do that other animals cannot is start fire from nothing.”

Samantha Harvey [3]

Martin Constable is attracted to crashes and ruins. His obsession with destruction partly stems from personal trauma, but also from seeing it as a process that reveals the structure and true nature of things [4].

For example, Rebes Minor (2021) takes half of its title from how astronomers name constellations. The decaying ruins, inspired by medieval castles from Game of Thrones, tell a satirical story of a competing academia from another world where teachers are killed and schools are burned [5]. But within this darkness, a small ray of hope, a flickering light, is placed in the center.

Many of the paintings selected offer a ritualistic scene of watching and highlight the importance of light. Lustrum (2024) presents a lone figure staring into a fire, humanity’s earliest technology. To master the control of fire was a monumental leap, the same as sending humans into space. To stare into light sources, albeit a candle, or the moon, is also a symbolic gesture [6]. A collective gathering to gaze at something together, as in Raze (2024) and The Invention of Grief (2024) is even more momentous. In this context, these paintings become contemporary rituals.

Lastly, What He Left Behind (2025) is a simple first-person view of a planet. It recalls the historical photo Earthrise (1968) taken by Astronaut Bill Anders from the Apollo 8 mission. Anders famously remarked that "We went to the moon to explore the Moon, but what we discovered was the Earth." The painting stresses this same profound moment, triggering a humbling awareness of our small presence against the cosmos.

Coda

A selection of works for What Cannot Be Forgotten, Must Be Celebrated delves into dark emotional states and somber scapes, excavating a deep contemplation on existence, while inviting us to confront the same questions for ourselves.

This contemplation culminates in the final piece, Qua-Auq (2015) where Constable digitally recreates the skull of Lam Qua (1801–1860), a Chinese painter known for being the first to adopt a Western style for his medical illustrations. By placing the skull in a vitrine that references the National Museum of Singapore, Constable again examines the very existence of the artist and the human desire to be remembered, and to leave something behind.

Earthrise taken by William Anders on Dec 24, 1968. Image credit: NASA. [7]

1. William Safire, "In Event of Moon Disaster," memorandum to H. R. Haldeman, July 18, 1969, Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, National Archives and Records Administration. Source: https://www.archives.gov/files/presidential-libraries/events/centennials/nixon/images/exhibit/rn100-6-1-2.pdf, accessed 2 September 2025.

2. Martin Heidegger used Vangogh’s Pair of Shoes to illustrate his point that art reveals the “truth of being,” because the shoes belong to a peasant woman, the image alone in a phenomenological sense reveals another world that belongs to the peasant, therefore the shoes are not just objects, but “equipmental being of equipment,” belonging to another context (1936). While Meyer Schapiro criticized Heidegger that the shoes were not of the peasant’s but Van Gogh’s own, therefore biographical (1968). Derrida criticized both of them that they viewed the shoes from a lens trapped in representations and imposing meanings onto the shoes that they must belong to a specific, rather than seeing the art in its own right. In this debate, Evan’s photograph of actual boots from the Great Depression is frequently used in comparison with Van Gogh’s, since it belongs to a person, while Van Gogh is a painterly representation. Source: Brian Goldberg, “Two Boots and Four Portraits,” RISD Museum, January 28, 2019, https://risdmuseum.org/art-design/projects-publications/articles/two-boots-and-four-portraits. Accessed September 2025.

3. Samantha Harvey, Orbital (London: Jonathan Cape, 2023), 106.

4. Martin Constable, interview by the author, online document, July 2025

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Earthrise: A Conversation with Apollo 8 Astronaut Bill Anders, December 29, 2023, video, https://plus.nasa.gov/video/earthrise-a-conversation-with-apollo-8-astronaut-bill-anders. Accessed 6 September 2025.

Interview with the curator Pojai Akratanakul for the exhibition ‘What Cannot be Forgotten, Must Be Celebrated’, BUG Gallery, 2025

Thai original is here.

Thai original is here.